The Man behind the Maps

‘Don’t worry! My health is excellent. If I have gout, it’s only in my feet and I flatter myself with the idea that I am completely free of it.’ Henriette breathed a sigh of relief. She had to be now that she had read those reassuring words in her husband’s letter. She was an aristocrat from the Austrian Netherlands, her family owned the Château d’Ursel in Hingene and had furnished it as an elegant summer palace. Joseph Jean François de Ferraris (1726-1814), a high-ranking military officer within the Habsburg Monarchy, was a regular visitor. It was love at first sight or almost, Ferraris adored Henriette d’Ursel (1743-1810).

The sound of the name Ferraris betrays an Italian origin. The path his ancestors had taken was therefore long and circuitous. But ancestors with a name helped you get ahead in life, and after many migrations Ferraris was born at the ducal court in Lorraine, after which he spent most of his youth at the court of Vienna. A military career was the logical next step. Ferraris entered the service of Empress Maria Theresia. He fought many wars for her afterwards until he finally ended up in the Austrian Netherlands. Here the future seemed to roll out effortlessly for him, his marriage to Henriette was a decisive step in that direction. Not that the wedding gave him much fame, Ferraris acquired his greatest fame as the aristocrat-entrepreneur who ensured that the Austrian Netherlands were mapped. Between 1770 and 1775, a hundred artillerymen left from the barracks in Mechelen, or from the training camp in Bonheiden, to cross the Netherlands and measure every element of the landscape on a previously unseen scale.

The result of the land survey surpasses all imagination. Anyone who looks at the 275 meticulously drawn map sheets is always amazed at what is recorded. The buildings in pre-industrial Belgium, the cities and villages with blocks of houses, parks and gardens are connected by the modern road network, and the 18th-century surveyors did their best not to lose sight of mills, pillories, shooting ranges and so much more. Every estate, every castle, sometimes even a smaller, old farm with adjacent plots, can be found with a little searching. The map is an unparalleled reference. It is the map of our past.

The surrounding nature is even more important today. Polders, dunes, peat bogs and forests bear witness to the landscape and land use in the ancien régime, i.e. before the industrial revolution had an impact on it, which makes the Ferraris map the benchmark for every place where the land use has remained unchanged since the eighteenth century. A forest remained a forest, and even though trees were of course cut down, the fact that a place remained continuously forested since the map was drawn up, now makes it a ‘Ferraris forest’. Ferraris forests therefore have a long history that probably goes back much longer than we can imagine.

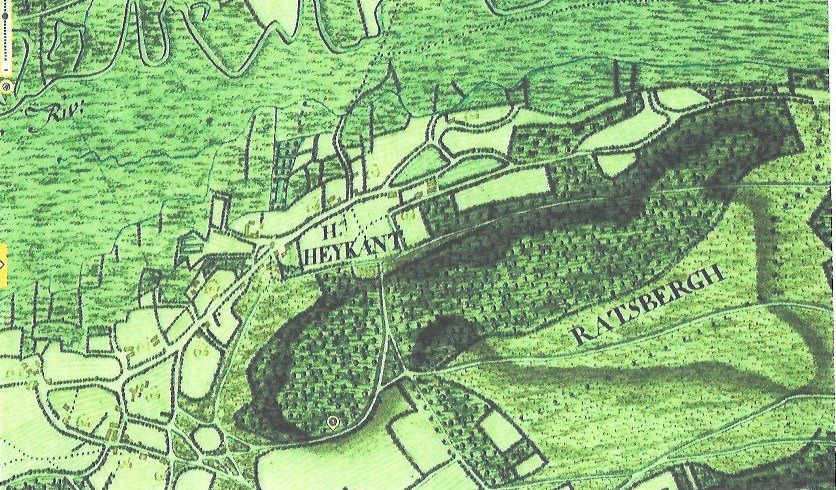

The Heikantberg in Rotselaar is a good example of this. It took centuries to grow into a stable ecosystem together with the neighbouring Middelberg. This is not only important for the experience of nature, the Heikantberg also owes its landscape value to its natural wealth. The forest floor contains an enormous seed bank with a germination capacity that can maintain the many typical tree species of the old forest.

But there is more. Since the 13th century, the Heikant forest probably supplied wood for the wine stakes of the neighbouring vineyards and the wine was also aged in barrels of Heikant wood. Later the grapes grew in the heath and on the southern slope of the Rodeberg, which is indicated on the Ferraris map as Ratsbergh, now the Heikantberg. At that time, the Rotselaar wine could still breathe peacefully in barrels made of Heikant wood. But the wonderful vineyard disappeared over the years. On a map from 1605, only the wooded ridge and the heath at its foot can be seen.1 Nevertheless, the contours of the ducal forests remained virtually unchanged until the end of the Ancien Régime, when the artillerymen of the Austrian Netherlands mapped them.2

Ferraris loved wine - more than was good for him, as is evident from his gout - but he was also a bit of an ecologist avant la lettre, always concerned about the landscape that suffered from the war. He would undoubtedly have been delighted with the Heikantberg. Because even though the Heikanthout no longer lets Rotselaarse wine breathe, the forest still offers its lungs to the residents, to hikers and nature lovers.

Ferraris chose a balanced life, combining his public functions, his service to the Habsburg court, with an intimate, personal life. Nevertheless, the balancing artist faced major challenges in the revolutionary period that followed.

_______________________

1 Plan du bois de Middelberg et Raasberg à Rotselaar, par Jacques de Bersacques. 1605. ARA I. Plans Série J .. Nr. 1 - 500.

2 Minnen, B. Nieuwe gegevens over de heerlijke wijngaard en de Heikant- en Middelberg te Rotselaar, 15de-16de eeuw, HOGT (Haachts Oudheid- en Geschiedkundig Tijdschrift)16 (2001), 184-198.